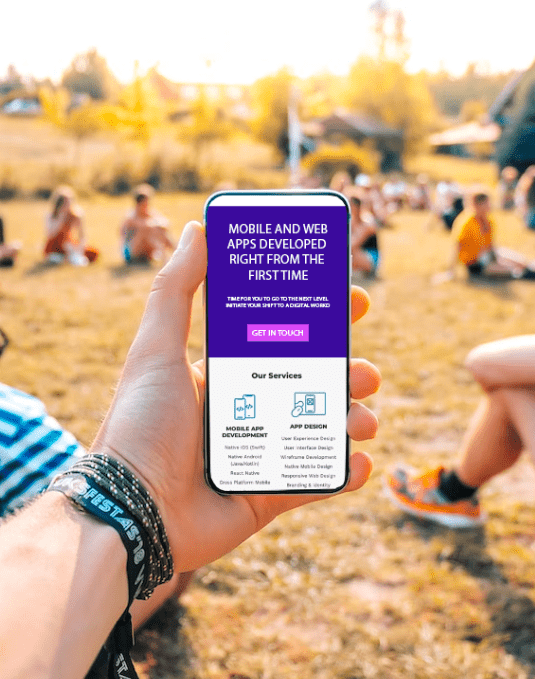

Mobile and web app creator

We create software that will adapt to your organization,

not the other way around.

Evaluate your project

Our Clients

We’re proud to partner with great companies and institutions

Why Choose Us

Link Software develops your next application

WEBSITES & WEBAPPS

You have a creative idea and you are looking for an agency to develop your website or web application? From the specification to the promotion of your website, through the design (UI – UX) and programming, Link Software accompanies you in the realization and development of your website.

![]()

Mobile APPS

Create your own custom mobile application. Our expert team of developers and designers work closely with you to bring your unique vision to life, delivering high-quality and user-friendly apps that enhance customer engagement, increase revenue, and streamline operations.

Discover our way of doing

No better place to start than the beginning.

Everything you’ll read, trickles down to a real understanding of what you want to achieve

Start with you

Finding out what you are trying to do or achieve is vital to set up the right product team

Discover and challenge

As we move forward, we gain clarity and will start elaborate yoru product and help you with complexity

Design with value

The value of good design is the increased possibilities of success for your project

Deploy and fly

Validate assumptions, deploy and test. We deliver value and collect valuable information in deploying fast

Deliver Quality

As we move forward, we gain clarity and will start elaborate yoru product and help you with complexity

Plan and report

This is the key to achieve quality and predictability in costs and value

What They Say

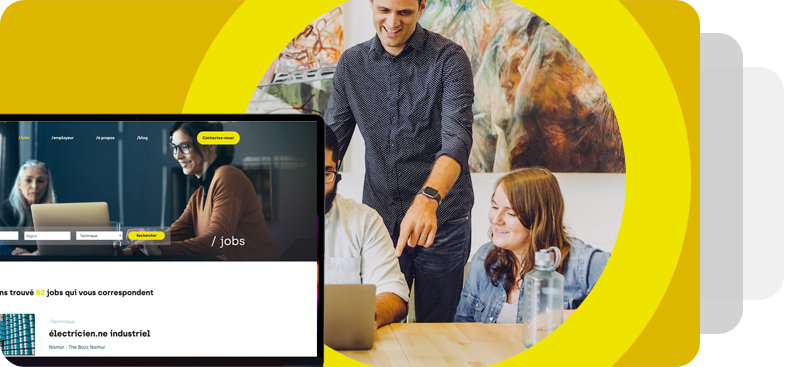

“Understand our business and its specificities and make it simple. That is Link Software”

With Link Software we found the partner who understood us and was able to translate our needs into a real effective digital solution.We are publishing job boards and needed to optimize the management of all our classified ads for the team. Link software quickly implemtented the right solution at an affordable cost.We are using our software on a day-to-day basis and are very happy about it.

Alexis Remacle

CEO Thebozz

“Understand our business and its specificities and make it simple. That is Link Software”

With Link Software we found the partner who understood us and was able to translate our needs into a real effective digital solution.We are publishing job boards and needed to optimize the management of all our classified ads for the team. Link software quickly implemtented the right solution at an affordable cost.We are using our software on a day-to-day basis and are very happy about it.

Alexis Remacle

CEO Thebozz

“Understand our business and its specificities and make it simple. That is Link Software”

With Link Software we found the partner who understood us and was able to translate our needs into a real effective digital solution.We are publishing job boards and needed to optimize the management of all our classified ads for the team. Link software quickly implemtented the right solution at an affordable cost.We are using our software on a day-to-day basis and are very happy about it.

Alexis Remacle

CEO Thebozz

We build apps for

expect your business needs to be understood and catered to. Our experience lets us find practical solutions to satisfy all kinds of requirements and budgets. We build software with scalability in mind, so your application will work for you long-term without additional investments.

Large businesses

With a modular approach, we build apps that can be easily tweaked and updated to the frequently changing market. Modular architecture also ensures quick maintenance, which is crucial for enterprise applications. Our apps are lightweight and handle high loads thanks to smart infrastructure and architecture choices. We prioritize security and perform multiple testing throughout the entire development process.

Small & medium businesses

For fast development and minimal rework, we focus on clear communication and thorough planning. Our project managers ensure you get a unique product with a thought-out architecture adherent to the latest technical standards. At the same time, we understand your possible concerns regarding timeframes and budget. So we develop a strategy to give you an effective solution with the shortest time to market possible.

Startups

To meet your need to provide excellent UX to a wide audience, we use the latest technologies for fast development. At the same time, our applications work and look consistent across all OS. Throughout the development process, we do multiple quality tests to eliminate post-development rework. Also, if your timeframe for an app release is really tight, we come up with an application versions plan to maximize your ROI.

Get our Free guide to write your requirement

We have developed a template that will allow you to build your specifications. It will be your guide to crystallize your ideas and help you organize your project.

[contact-form-7 id=”3995″ title=”Subscription”]